China's Next Steps After COP21

Hailed as one of the greatest diplomatic efforts of the past 30 years, 196 countries came to an agreement on December 12th at COP21 in Paris, to take steps to reduce the risk of a global temperature rise beyond 2 degrees. An effort that once again went down to the wire, the agreement represents the start of a long road towards climate change mitigation. It’s a road that many are already calling unrealistic, but for others the agreement itself was a major achievement because it’s the first time that all the major parties, including the United States, were able to reach a consensus.

It’s a framework that has imperfections, particularly because it’s non-binding and void of specific steps that need to, or will, be taken. However, make no mistake, this agreement should be seen as a solid foundation that will lead to action .

For many, the hard work starts now, but for the US and China, this can be seen as a continuation on the work that resulted in the September US-China Joint Statement on Climate Change. It provided a framework that will ensure that developing countries, like China and India, will (re)set the models for how their countries will try to prosper over the next 35 years, whilst developed countries and regions like the US and EU will look more towards how they can clean up their already mature economies.

It’s a framework that in many ways represents what many had hoped would be agreed on in Paris, particularly on areas of emissions commitments, technology transfer, and financing mechanisms.

Going forward though, and in considering the challenges that will be faced as China drives to urbanize another 300 million people by 2030, the agreements made in Paris lay the groundwork for five specific actions:

Reduction in energy intensive industries

As China draws closer to 2030 and the end of its large-scale urban development, which for so long has been the basis of its economy and energy use, its footprint will naturally begin to decrease. With the urban centers well established and growth of its urban population stabilizing, energy intensive industries such as cement, steel, glass, and aluminum will be replaced by a greater contribution of the service economy, and reductions in resources (energy) intensity will be seen throughout the economy.

In fact, natural reductions likely underpin China’s confidence that its emissions will peak in 2030 .

Increased investment in cleaner energy systems

While there have been reports over the last year that China’s coal energy production levels have come down, it’s important to remember that in the short term coal will be China’s primary fuel . Any divestment from coal will come later. In fact, in the last 12 months, over 150 plants have been approved across the country, which will ramp up consumption capacity.

This doesn’t mean China will forgo the targets set out in its agreement with the US. China now leads the way in renewable investment and nuclear installation, but before King Coal is officially declared dead, changes will come through large scale restructuring of the energy industry, increased investment in renewables, improvements in grid connectivity and production side efficiencies.

This doesn’t mean China will forgo the targets set out in its agreement with the US. China now leads the way in renewable investment and nuclear installation, but before King Coal is officially declared dead, changes will come through large scale restructuring of the energy industry, increased investment in renewables, improvements in grid connectivity and production side efficiencies.

Investments in energy efficiency

This is an area I have addressed in previous blogs. I view this as one of the areas where China has the most potential to see returns and one that is a vital component in the country’s hope of achieving peak emission in 2030.

In fact, in the US-China agreement it was pledged that 50% of new building would be green by 2030. With a large portion of energy consumption coming through energy efficient buildings and cities, the opportunity to mitigate (or even reduce) the energy load required will come through better urban planning, better building standards, and continued retrofitting of existing buildings. This is also likely an area where technology sales/ transfers to China can happen!

Adjusted resource pricing

Adjusted resource pricing

In the final draft of the agreement there was an emphasis on educating the public on the issue of climate change and sustainable development. Whilst this is a nice sentiment, it’s not going to lead to strong enough behavioral change in the short term.

Within China, we see change coming from the rising cost associated with the consumption of energy. People will not be driven to change unless it directly impacts their daily lives , through convenience or economic and financial implications. Recent announcements by China’s National Development and Reform Commission and the National Energy Administration to move energy pricing to a more market-orientated system support this point. This is a clear signal that the State sees increased cost of energy to residential, commercial and industrial users as a way to change behavior .

Increased transparency leading to effective legal implementation

Whether driven by its own research showing the impact of pollution on its soils, or increased public concern over the impact air pollution has on urban residents, there has been a clear behavioral shift by the Chinese government in recent years .

It started with statements about needing to find a balance, resulted in the promulgation of new laws, forced the closure, fines, and arrest of those in violation of laws, and has also been behind the government’s decision to release PM2.5 data for China’s major cities.

In this area, particularly given that challenges are likely to grow in size and scale as China (and the rest of Asia) urbanize another billion people, it can only be expected that the level of interest (and activity) by the government will increase. At times that interest may not feel sustainable, but none the less it has the power to negatively impact the operations of firms in China.

Conclusions

In reality, while many keeping a watchful eye on COP21 were looking for China (and others) to go above and beyond the call of duty, for China the big commitment was made with the US in September . PM2.5 remains a major problem in China’s cities and is the driving force behind civil concern and energy restructuring, and the actions explained above are seen not just as a way to reduce carbon, but to provide energy to Asia’s billion urban residents without choking its cities.

With much of the above already rumored to be incorporated into the upcoming 5-Year plan, it is clear that whether through the COP process, as part of its drive to reduce PM2.5 emissions, or to feel secure about its energy supplies, China is actively taking steps to identify and address the challenges that its energy system faces . This is a system that is currently adding more power to its grid than all of Europe, every year, and is projected to more than double in size over the next 15 years.

So, while nothing in COP21 is legally binding, I think that in combination with the US-China announcement, China has already begun a process of transacting on commitments to bring emissions under control. It may not be coming out of a sense of moral obligation to the global climate, but perhaps that is why many view China as one of the leaders. Because, beyond the emotions behind the issues, concrete actions are being taken in China every day .

The Next Big Thing For Entrepreneurs

[In] the last century [the thinking was], if you wanna grow as entrepreneurs, you should find a good opportunity. But today, if you want to be a great company, think about what social problem you could solve.” – Jack Ma, Founder of Alibaba

When looking for leadership on sustainability, and for those who are going to deliver the solutions that are needed, the search typically begins with big businesses like Wal-Mart and Unilever and their leaders. The search tends to focus on firms, and leaders, who have large platforms from which they can announce their commitments to changing products, processes, and people as they execute their vision for sustainability. At times these announcements have been backed up by significant investments in time and energy.

However, as the challenges of maintaining balance between economy, environment, and society has grown more difficult to maintain, it is the role of the entrepreneur as visionary and solution provider that has begun proving the power of business, and markets. They have the power to not only solve crises, but to create a new business model. One that starts with a vision of sustainability at the core, and captures an ecosystem of customers along the way that shows that a “sustainable business model” isn’t an unprofitable one.Take for example the food sector, one that is rife with consumer scandals and resource challenges in China, where large brands have been largely focused on risk mitigation, resource efficiency, and crisis prevention. For traditional “big food” players, the challenge is compounded by the size and scale of their supply chains plus the speed with which China, and other markets, is growing. Firms need to identify, assess, and engage tens of thousands of farmers on one end of the value chain, while creating thousands of new distribution points that will deliver product to the market on the other. There is no time to slow down or go back to do things “right”

For the Hong Kong-based OceanEthix, their aquaculture (fish farming) systems were built with sustainability in mind in an industry that is known for numerous environmental impact, social, and consumer safety challenges. Their system, one that is closed loop and modular, has water efficiency, transparency, and product quality at the core of its design, and their modules are now being deployed at various sites in Asia. For the Shanghai-based FIELDS China, a food delivery platform, it was a business model born from the entrepreneur’s own experience with trying to find clean, safe, food for his family, and has quickly grown into a multi-million dollar business that is scaling into China’s second tier cities.

Entrepreneurs that once occupied the long tail of the economy, and applauded for being “nice” as a result, are now gaining the interest of “traditional” business as they are now seen as market leaders . Leaders who have created products and services with loyal ecosystems of consumers, and markets that are moving from niche to scale. Dynamics that are leading to a shift in mindsets across the board:

- Business leaders are looking at social issues as new markets, and successful social minded enterprises as potential investments .

- Consumers have begun looking for safe, reliable, high-value products, and more importantly they are showing that they are willing to pay a premium for them.

- Employees are now willing to leave comfortable lifestyles and jobs behind for the prospect of building a new model for change.

- Governments are now investing significant time and energy to help solution providers incubate and scale their business models, while looking for ways to decouple their economies from models that are seen as risky, resource intensive, or destructive.

These shifts are helping entrepreneurs validate their vision and markets, creating the awareness needed to help reach consumers, bringing economies of scale and profit, and most importantly bringing exit opportunities.

As China’s economy transitions towards maturity, where conversations of “balanced growth” replace those of “growth at all cost”, the opportunity for entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs to develop new markets for sustainability has never been better .

It is an opportunity being supported by consumers who are willing to pay a premium and governments who now understand that the challenges that have plagued them for years have become a threat to their development models. For those who are able to meet this need, China will only be the start.

Reframing Sustainability For Future Cities

For the first time ever (as of 2012) more people – over 700 million – live in China’s urban areas than in its rural regions. By 2020, about 60% of China’s population will live in cities; and 300 million urban residents are expected to move into its urban centers by 2030. Along with this shift to a more urban population comes a dramatic change in lifestyle: from a subsistence level or an agrarian focus to a consumption-focused lifestyle.

For the first time ever (as of 2012) more people – over 700 million – live in China’s urban areas than in its rural regions. By 2020, about 60% of China’s population will live in cities; and 300 million urban residents are expected to move into its urban centers by 2030. Along with this shift to a more urban population comes a dramatic change in lifestyle: from a subsistence level or an agrarian focus to a consumption-focused lifestyle.

Sustainability in China has been a topic of many conversations for years now. The failure of China and the US to come to agreement in Copenhagen in December 2009 focused even more attention on the topic. It is a story that has been about smoggy skies and polluted skies, and as the challenges have grown, calls for a different model have grown louder. It is a story that has gained more steam over the last several years as urban residents have become more numerous, grown wealthy, and are increasingly impatient with the smog.

On February 28, Chai Jing, one of China’s most famous television journalist and a best-selling author, released a self-financed documentary aiming to unveil the root causes of China’s notoriously polluted air. The 103-minute video quickly went viral, and within days of its release it had been viewed more than 200 million times. Some began calling Ms. Chai China’s Rachel Carson, an American activist whose book The River Runs Black was seen as a turning point in America’s environmental movement. Others compared the video to Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth.

For many foreign firms operating in China, this change in dynamic has often been seen as a threat as regulatory bodies and their enforcement arms have increased their efforts to curb pollutants. For others, the changing dynamic has been a source of hope. It’s a sign that China’s new markets for green energies, building materials, and electric vehicles – which are growing faster than anywhere else in the world – are being driven by a wider body of stakeholders that are accepting that China’s environment is failing and that change needs to happen. Change is beginning to take place. A change that, if made, will over the coming decades see the development of sustainable urban environments becoming one of the greatest economic opportunities of our lifetime .

Looking at the issues of sustainability in the context of China today, it is of primary importance for outsiders to understand the following:

- Historically, China’s issues of sustainability were not linked mainly to private consumption, as they are in the United States or Western Europe; they were linked to the industrial processes that are supporting China’s economic development model.

- China does not see emissions as a “problem” that must be dealt with immediately . With economic growth still the priority , the country’s concerns with sustainability are focused on accessing and managing the resources that its cities will need to grow, while reducing the emissions that are contaminating its air, water, and soil.

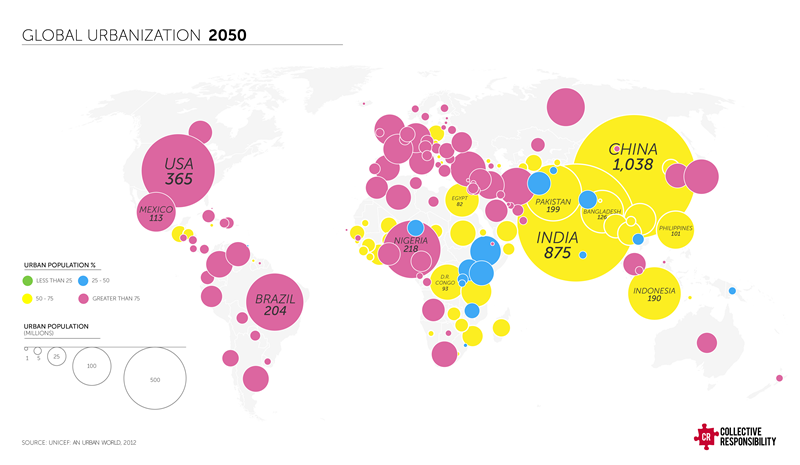

- The largest pressure China faces to solve sustainability issues will continue to come from within, as the next 25 years of growth will come from another 300 million moving to the city .

Simply put, the issues that China faces are largely tied to economic development , the problems themselves are growing in size and frequency, and China will do what it takes to fix those problems in a way that considers the needs of its people first. These are also issues that will continue to be faced by India, Brazil, Nigeria, and the next generation of cities that will go through hyper-development over the next 25 years. Leaders need to stop seeing sustainability in China as a threat to doing business , and begin seeing it as an opportunity to develop a portfolio of products and services that will support the urban centers supporting billions.

Areas where there are immediate opportunities and need:

- Urban Planning – At the core of a sustainable city is the urban planning, and sustainable cities are often viewed as the only way that a population of 10 billion people on Earth could be sustained. They need to be dense. They need to be efficient with resources. But more importantly they need to be places where people want to live, raise children, and invest in their communities.

- Energy distribution and efficiency – While the focus of many conversations in the energy industry is around cleaner energy supply, for China the real need is to drive efficiency through the grid – a grid that requires up to three times the amount of energy it takes Western markets to create one unit of GDP.

- Food safety – Whether it is through the acquisition of firms like Smithfield Foods, or through partnerships with IMB to create pork traceability programs, one of the key areas for improving the urban economy will be through food . With an estimated 40-60% of China’s food lost before it reaches the tables of its consumers , it is an industry whose inefficiencies begin on the farm and continue through the entire food chain .

- Accessible and affordable healthcare – With China’s population graying, and its urban environments struggling to provide care to its sick and aged, mayors around the country are already looking to industry to bring solutions that build on top of the government’s own capacity to build care facilities .

- Efficient Transportation – As consumer demand for private vehicles continues to rise, a variety of alternatives are being developed to address the challenges. The automotive industry is focusing on broad innovations (including electro-mobility) to decrease fuel consumption and reduce the emissions of public and private vehicles. At the same time, advances in technology and investments in infrastructure have the opportunity to make public transport a more viable, efficient alternative.

- Waste Management – As China’s material consumption continues to increase, the level of waste production will only increase the amount of organic and inorganic waste that is entering landfills every day.

Where this gets exciting for those in China, is that once a product or service’s pilot project has proven itself in China, there will be an opportunity to scale to the country’s needs through the markets of India, Brazil, Indonesia, and Nigeria . These are the cities of the futures for hyper-urbanization, and will be critical players in a world where there are 6 billion urban consumers looking to live the “American Dream”. It’s a dream that is only possible through a new model, one that will be sketched out in China and fine-tuned over the next 35 years.

Throw The Old Rules Out The Window

Changes in China’s environmental rules and regulations, the first revision in 25 years, take effect January 1 next year with stiffer penalties for companies that flout the law. In recent years, as well, there have been a number of cases across the country where residents’ objections, because of environmental concerns, have led to major projects being scrapped. China, it appears, is now getting serious about finding an economic model that balances social and environmental needs and this will change how business is done .

The Chinese have joined ordinary people all around the world who are being catalyzed to take action against firms that are polluting their air, water, or undermining their local economy. Consumers are being catalyzed to take action against companies whose products are unsafe or practices are unfair. Governments are being catalyzed to improve standards, largely in response to the actions of citizens and consumers, and this increases the cost of doing business. This is why, for executives leading global firms, large or small, it’s more important than ever to rethink their vision and value chain when it comes to sustainability .

For years, investments in CSR and sustainability programs were touted as the best way to create engagement and insulate a brand. But those investments are often separate from the core business; so when failures snowballed into a call to action, the short-term nature of these programs quickly showed through. Going forward, companies will have to break through this cycle if they’re going to keep up with, and stay ahead of, the changes in regulation and consumers’ expectations.

To do this, business leaders must understand the need for recalibration at the very core of their organizations. This would be a major shift that moves a firm from the mindset that ‘compliance and good CSR is merely strategy’, to one where a new vision for the firm is born, risks are removed entirely, and new market opportunities are identified, innovation created, and stakeholders are engaged.

In this scenario, no templates exist. The issues are intangible and, depending on each firm’s structure, industry position, and capacity, it will need to develop something highly customized. But, in general, there are 6 steps to making this change:

- Rethink: Explore and analyze your value chain to identify areas of risk, opportunity, and action. For many firms, this is a critical first step. It provides the data needed to identify and understand the issues of environment, society, and economy that will challenge the value chain. These are challenges that will force leadership to scrap boiler plate definitions of sustainability, and create customized, tangible, definitions.

- Re-Vision: Be committed to a crystal-clear vision and purpose. In the cases of Unilever, Interface, Whole Food Markets, and many others, this vision came from the CEO and/or founder, who had to personally drive the move forward. For Ray Anderson, founder of Interface, the process has been ongoing for 20 years. Before his passing, Anderson had built the capacity within Interface’s ranks to maintain their path towards summiting “Mount Sustainability” and achieving their 2020 goals of zero waste and zero virgin material usage.

- Restructure: Create a blueprint for implementing your ‘re-vision’. Redesign products so that unnecessary processes can be eliminated, so that usage and waste of material can be reduced. This, in turn, leads to a restructuring of equipment specification and buying practices. It also means positively engaging employees, suppliers, and customers in the journey towards ‘good’.

- Realign: Strategy needs to be closely aligned to stakeholder needs, interests, and capacity. Review where you make your investments for long-term engagement. Short-term CSR exercises are a good start. But for the recalibration to have maximum impact, these engagements need to focus on how stakeholders up and down the value chain see where the firm is exposed, where opportunities for collaboration exist, and where there are new business opportunities.

- Recalibrate: Conduct a series of pilot projects that are meant to test, tweak, and prepare for a systemic recalibration of the firm over time. Interface is 20 years into their process; Wal-Mart and Unilever are both five years into theirs. It will take time, and experimentation, to get the mix right. For those firms that have completed the first four steps, this is when innovation and an innovative culture will begin to bear fruit.

- Remain Committed: Building a ‘good’ business demands the wholehearted adoption of the process, and a commitment to taking steps forward in realigning the firm’s vision, value chain, and product offerings.

Ultimately, leaders need to understand that, going forward, the issues of sustainability and CSR will become more vital to their business as the negative effects of “business as usual” increasingly disrupt the lives of their stakeholders.

This understanding will push them to take up the challenge to recalibrate their firms towards a new model, a model that is not a complete tear down of their old approach – or predicated on worst-case predictions of environmental collapse. It’s one that’s built on solid foundations of understanding how issues of environmental, social, and economic exposures map into their value chains. It’s about re-visioning their business to remove those areas of vulnerability, and then taking the steps necessary to move from inspiration to action.